| Despite a defeating year for investors all around, there’s actually one place you could’ve found a double-digit return on your money—the US dollar. Bucking a historically inverse relationship, the dollar has found resilience even under high inflation conditions. But it’s causing more harm than good. Why is the dollar going up? The dollar is rising in the face of conventional wisdom because of the unique situation the global economy is in. All economies are suffering the whiplash of the pandemic, but the US may be the most resilient, with the dollar being a perceived safe haven and the world reserve currency. And with rapidly rising rates that create more attractive yields on reliable debt securities, we’ve got a recipe for dollar strength. The fallout—mostly bad, but some good - Good—inflation & imports: A strong dollar’s dent in inflation is tough to measure, but we’ve observed some noteworthy impacts. Research from earlier this summer shows that the dollar’s 10% rise against its trading partners’ currencies resulted in an effective inflation reduction of just about 0.4%. Not much relative to its 8.3% spike over the last year. All-in-all though, the difference is negligible for us at home, and the real benefit comes from imports, which get exceedingly cheaper as the dollar’s strength rises.

- Bad—earnings & exports: Counterintuitive as it might seem, a strong dollar is bad for US multinationals who derive a lot of business internationally. On one front, a strong dollar makes US goods more pricey, so consumers and businesses abroad will seek alternative sources, denting revenue a bit. Also, profits get further diluted when they’re converted back to a strong USD—one year ago a Euro was worth $1.18, and now it’s worth just $1, a 15% drop.

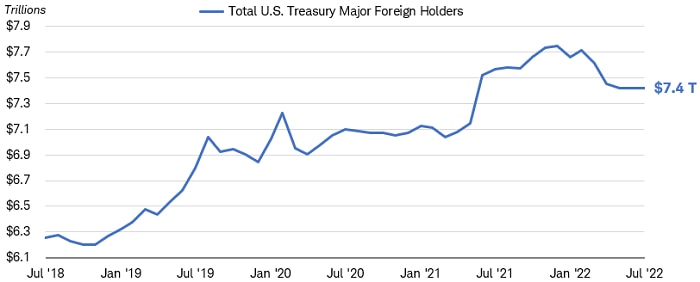

Closing out the year A strong US dollar poses a threat not just to US companies, but elsewhere too. Analysts fear that the dollar could also be a threat to other economies. As some of the world’s most important goods like energy are traded in dollars, a strong greenback makes tackling inflation abroad even harder and gives central bankers a conundrum on whether or not to raise rates faster or slower. Barring some kind of intervention, there doesn’t currently appear to be an end in sight to this dominance though. Foreign holdings of US treasuries are sitting pretty, emerging market securities still boast negative yields, and the US continues to look like the safest of safe havens during these weird times.

Source: Schwab

Take this related lesson on this topic and earn Dibs 🟡 while you're at it:

|