| It's that time of year again, and we're not talking about fall. Every year, the US government starts a new fiscal year on October 1st, and nearly every year, we have to make adjustments to the debt ceiling in order to keep things afloat. Technically, the government topped out its borrowing power back in July. Thankfully though, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellin has been moving money around with "extraordinary measures" like Marty Byrde in Ozark to keep the government running. Gotta love accounting. The debt ceiling has been increased almost 80 times since 1960, and it's become an almost annual affair for Congress, but it wasn't always this way. The stuff they didn't teach us in Econ 101 The debt ceiling came into existence back in 1917 thanks to the Second Liberty Bond Act, which capped the amount of "Liberty Bonds" the US government could issue at an aggregate total of $15 billion. We were using this debt to fight World War 1, and policymakers never dreamed it was a limit they'd actually hit. Little did they know. The US is also one of the only countries that imposes this situation on itself, as not all countries maintain a moving debt limit. Poland is the only nation with a constitutional statute enforcing it, set at 60% of GDP. On top of this, the historically routine situation has become increasingly political over the last couple decades. Although raising it is the only real option outside of minting a trillion-dollar coin, no party wants to take the blame for being the ones to "pile on more debt" anymore.

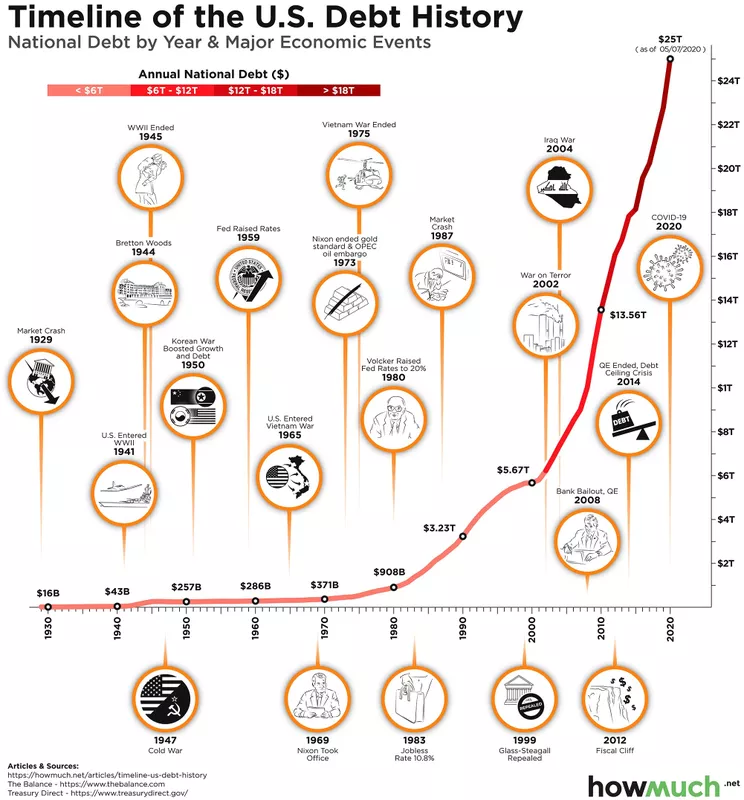

Source: Howmuch.net How does the debt ceiling affect us? Economy: The United States debt has a butterfly effect on our entire economy, and potentially the worldwide one as well. Being that we've not once defaulted on an interest payment, any failure to do so at all would stoke fear in borrowers everywhere, both private and public alike. Rates: When borrowing money from the US becomes riskier, bond yields increase, which subsequently ends up increasing all the other rates across the financial system. Interest rates on all kinds of borrowing from mortgages to credit cards rise, making it less appealing and less affordable for people to borrow money. Markets: Most of us probably aren't buying bonds, but institutional investors, pension funds, states and municipalities, and other countries do. When the return on said bonds is forced to rise, parking money in a "safer" alternative to equities becomes more appealing, moving money out of the markets. Stocks then take a double hit simply because of social sentiment and the fact that retail investors perceive it as negative. |

No comments:

Post a Comment